The deadline for the Part-time Remote Research Assistant positions has been extended to Friday, 25 July 2025 (please ignore date in original add below).

For more information, visit http://shorturl.at/pX6Wp

The deadline for the Part-time Remote Research Assistant positions has been extended to Friday, 25 July 2025 (please ignore date in original add below).

For more information, visit http://shorturl.at/pX6Wp

On June 21 2023, representatives from the GLU once again travelled to the Bacchus’ Library, Affiance, Essequibo Coast, Region 2, to facilitate a two-hour workshop on Creolese for the 2023-2025 cohort of American Peace Corps volunteers.

Each cohort of Peace Corps volunteers usually serves for two years in the health, education and environment sectors in Guyana. Before travelling to their allocated sites, the volunteers are sensitized to key issues in Guyana, such as health, safety and security, language and culture over a ten-week training period.

Charlene Wilkinson, Coordinator of the GLU, gave a general overview of the political dimensions of language issues in Guyana at the start of the workshop. Bernicia Chekema, a native Wai Wai speaker and GLU translator, then shared her experience of raising a multilingual family in Georgetown, as someone married to a native Creolese speaker.

Ronda Thomas, a native Creolese speaker and GLU translator from the island of Wakenaam in the Essequibo, brought a different perspective: sharing how she was able to overcome the prejudices against her mother tongue.

The celebration of International Mother Language Day was originated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and observed this year under the theme “Multilingual Education: a necessity to transform education”. The public ceremony which was organized by the Guyanese Languages Unit and the Amerindian Research Unit focused on the importance of preserving and making the nine Indigenous languages and Creolese official. The presenters proposed for these ten languages to be included in the school curriculum and all educational institutions in Guyana. The first languages of our ancestors need to pass down from generation to generation so that each person’s identity can be strengthened. Professor Paloma Mohamed Martin acknowledged the presentations by the translators and reiterated that she would work together with them to actualize their proposal.

This blog was written as part of an assignment for Use of English, a module within the Department of Foundation and Education Management at the University of Guyana.

This video addresses the need to respect and promote the Creole and indigenous languages of Guyana. It is an audio version of a letter presented to Ms. Letitia Wright, the Guyanese star of the film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, on the occasion of the ceremony at the University of Guyana at which she received an honorary doctorate. The letter was presented on behalf of the speakers of the nine indigenous languages of that country and of Creolese, the officially unrecognised national language that unites all Guyanese. The published version of the letter was subsequently published in the Kaieteur News newspaper.

Creolese

Dear Ms Letitia Wright, awi glaad yu kom.

(We are glad you have come.)

Akawaio

Saru eni man Letitia, pori’ pe esi e pi.enna’ posak pe’apata’se’ya’.

(Welcome Letitia, I am happy because you have come to your home.)

Arekuna

Wakope kuru auyesak mang.

(It is good to have you come.)

Kalina (Carib)

Gupalolipoh Dr Letitia Wright chohoe yapokuroe meh owupihoe eni guyana takamah gupah enyambabko owitoripa taroro Okuneh eropa eni pahotah.

(Greetings Dr Letitia Wright, welcome, I am happy you’ve come home to Guyana, have fun and enjoy your stay and do come back again after this.)

Lokono (Arawak)

Maburika to’shikwa Letitia.

(Welcome home, Letitia.)

Makushi

Miirîman, miirîman Letitia morîpe erepanki anna koreta.

(Welcome, welcome Letitia. We are so happy to have you.)

Patamuna

Wakù pe elepankà apata yak Letitia!

(Welcome home Letitia!)

Wai Wai

Kîrwanhê Mîmokye hara Letitia, tahworê so makî nasi amna amotopo poko awewtonthîrî pona hara.

(It is nice that you have come back Letitia, we are so happy for your return to your homeland (motherland))

Wapichan (Wapishana)

Kaiman wadapapan pugaru.

(We welcome you wholeheartedly)

Warau

Ina oriwakaiya, Letitia. Mitane atais tama hota ari. Boukaiya, Letitia.

(I am happy to see you back in the country Letitia. Welcome Letitia.)

Dear Ms. Letitia Wright,

We are delighted that you have taken it upon yourself to ‘rep’ Guyana everywhere you go and every time you get the chance. One area we Guyanese are not so great at either understanding for ourselves or explaining to the world is the question of our languages. We proudly pronounce that we are ‘the only English-speaking country’ in South America. Of course, we all know that the only language most Guyanese speak everyday with our families and friends and in our workplaces is Creolese. And some people like to fool us that it is ‘broken English’, ‘bad English’, or ‘just English with careless pronunciation’. Or we tell ourselves that it isn’t a language because people in Buxton speak ‘a totally different language’ to the people in the Corentyne, even though ‘mi doz swim in chrench’ means exactly the same thing anywhere you go in the country. Or we say that the way we speak cannot be written accurately only because we don’t know the writing system for Creolese and have never learnt it or been taught it.

To borrow from what the constitution of Haiti says about Haitian Creole, Creolese is the language which unites all Guyanese. This is a language created by our African ancestors in conditions of slavery, inherited by Indian, Chinese and Portuguese indentured servants, who have added words covering every single feature of culture, food, music and folk tradition that makes us who we are. English just happens to be, for now, the only language of the courts, government administration and formal education. That, of course, can change if we as Guyanese make it so.

And then there are the other Guyanese languages, the languages of the indigenous peoples of the country. The main ones are Akawaio, Arekuna, Karinya (Carib), Lokono (Arawak), Makushi, Patamuna, Wai-Wai, Wapichan (Wapishana) and Warau. These are the languages of the ancestral people of this continent who kept this country safe and sound for those of us who have since landed or were landed on its shores. Like Creolese, these languages pass down from generation to generation and make us who we are.

You are reported to have said that you regret ‘losing your Guyanese accent’. We know that behind that statement is regret at losing your native language, Creolese. You have not lost it. It is buried inside of you, under years of being forced to talk differently. But the language of your mother and grandmother lies within you, just waiting for you to dig it up and display it to the world. In fact, we hear it rising to the surface ever so often, like when you were reminiscing about your favourite Guyanese foods on Jumpstart radio. It’s just a matter of time, Ms Letitia, and a bit of practice.

We note the excitement of speakers of South African Xhosa, Mexican Yucatecan Mayan and Haitian Creole when they hear their long ignored and disrespected languages spoken in ‘Wakanda Forever’. The fact that the Black Panther movies show not only ‘people who look like me’ but ‘people who talk like me’ is important for the children of the world. We are lucky to have you at the centre of this. We can be forgiven for dreaming of hearing our languages in the next Black Panther sequel. These would be the languages of a hidden multilingual civilisation with a population made up of Amerindian, African, and South Asian people, using Creolese and the nine indigenous languages of Guyana. Maybe, they might use the knowledge embodied in these languages to create their own vibranium from scratch, with that mineral coming from their inner spaces, rather than from outer space. We have, of course, recently been gifted with the vibranium of the real world, oil and gas. But even as we play with the two-edged sword that is our vibranium, we need the inner understanding and acceptance of self which can only come with an acceptance of our languages.

We dream that you, as our representative can help us see and hear ourselves for who we really are. We dream that you, in the role you have adopted for yourself to ‘rep’ Guyana, can ‘rep’ the Guyanese languages too. We dream for you to become a patron of the Guyanese Languages Unit at the University of Guyana and carry our language torch to the world. We dream that that glow will reflect back on Guyana as we work in the dark to find ourselves beneath the rubble left behind by slavery, indentureship and colonialism. We know we are dreaming. But, in the world of the imagination, all things are possible. And all our languages have a word for ‘dream’.

We love you, Ms Letitia.

………………………………………………..

Charlene Wilkinson (Creolese)

Trevon Baird (Creolese)

Charo Albert (Arekuna)

Cliva Joseph (Akawaio)

Akeem Henry (Kalina/Carib)

Skeitha Thomas (Lokono/Arawak)

Gloria Duarte (Makushi)

Ovid Williams (Patamuna)

Bernicia Chekema (Wai Wai)

Vivian Alex Marco (Wapichan/Wapishana)

Silverius Perry (Wapichan/Wapishana)

Derrick Henry (Warau)

by Charlene Wilkinson, University of Guyana

Republished from: Transforming Pedagogy: Practice, Policy, & Resistance (Sargasso 2018-19, I & II)

The uncountable moments that impinge upon a student’s consciousness, confined—even distorted as it can often be in these ex-plantation societies—to the shape of neo-colonial institutions, can indeed serve to energize an iconoclastic transformative impulse. By practicing that both cursed and blessed activity that some have referred to as “the art of memory” (Yates) or “inventing the truth” (Zinsser), we may indeed present an artform that breaks through time barriers with the sole intent of transformation.

Two of my earliest student memories are of my primary and early secondary school days. In the first memory, I am eight years old. I am standing in the school yard. Another student comes up to me and, in a menacing tone, says,

Yuu tingk yu wait, na! Yuu tingk yu wait! Wel, le mi tel yu. Yu een wait jos biikaaz yu doz taak so! Yu iz a Potagii! [Do you really think you’re white? Do you think you’re white? Well, let me tell you. Talking like that doesn’t make you white. You are a Portuguese.]

In the second memory, I am twelve years old. My British cousins are visiting from England and we are all sitting around the dining table after dinner chatting and laughing about everything and nothing when my otherwise gentle and loving Creole-speaking mother suddenly says to our cousins in her best English and in a deeply apologetic tone, “My children don’t speak as well as you, you know!”

There is a momentary silence at the table, but the talking quickly starts again. I would never ever forget the slap in the mouth I felt that evening, as real as though it were a brutal physical slap. And yet it was “forgotten,” and life went on, the moment disappearing into the beautiful mess that is life. Yet I can say that it was those two memories sitting side by side across the years that contributed to the emergence of the language activist, the “Afro-Asian-Euro-Indigenous” Guyanese* who eventually came to master the “White language” that the primary school child was singled out for and that her mother was in awe of.

The scientific detachment that often accompanies matters of “policy” and “human rights” clearly cannot alone drive the validation of Guyanese Creole and the further inclusion of all of Guyana’s languages as valid languages for teaching and learning in the school system. For the language aware teacher, being powerless in the face of language discrimination can be soul-destroying. Nowadays it is fashionable to give the condescending nod to Guyanese Creole and those Amer-indigenous languages that are still the mother tongues of many of our students, “Use them to facilitate comprehension.” But generally, teachers in today’s Guyana deliver an English-only curriculum.

The rage for English in Guyana has resulted in a nationwide school curriculum from nursery school through the university level that patently denies the linguistic genius of the nation. This denial further eclipses the various traditional knowledges of the people, relegating them to “folk customs” that may be studied as objects of anthropological consideration at the university and paraded during national cultural events.

A third memory, from many decades later, at New York University during

the 1990s, stands out, and accentuates those two childhood memories. I was enrolled at the PhD level in a programme called Educational Theatre. The course in question was called Drama in Education. One of our tasks was to design a set of drama structures to teach any topic in the school curriculum. The details are vague but what looms up, and again is informed by a series of related memories and experiences all the way from childhood to adulthood, is the power of drama to transform. Drama structures can provide the opportunities for both students and teachers to liberate the voices trapped inside the English-only curriculum. Can we envision a curriculum where the focus on English becomes more tightly concentrated on teaching it as a language for “wider international communication” and the focus on increasing drama structures in the curriculum becomes more tightly concentrated on promoting self-expression and engendering knowledge sharing and knowledge creation for nation building?

The spoken word in drama can then present the material for texts in Guyana’s native languages, none of which, to date, are present to any significant degree in the education system. This, to my mind can be the seedbed for curriculum reform. Who knows whether we cannot in fact, repair the house while we live in it?**

* In a personal conversation with Carinya Sharples, creative writer and freelance journalist, I was made aware of the ethnic description “Afro-Indigenous.” In some amusement, I labelled my own ethnicity thus.

** When Lawrence Carrington did a short spell–three years–as Vice Chancellor of the University of Guyana from 2009-2012 he described our task of reconstruction in these terms.

The entire issue of Transforming Pedagogy: Practice, Policy, and Resistance (Sargasso 2018-19, I & II) can be accessed via FIU’s Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC). Back issues are also available through dLOC. The issue is available for purchase in the College of Humanities at University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, or through Sargasso’s website. Sargasso is A Journal of Caribbean Literature, Language, and Culture.

Earlier in 2019, two members of Caribbean Yard Campus visited Guyana and met up with the Guyanese Languages Unit. But what is Caribbean Yard Campus? Educator Johannah-Rae Reyes explained more about what they do:

Caribbean Yard Campus is an educational enterprise that is designed to network traditional knowledge systems in the Caribbean. It functions as a partner organization of the Lloyd Best Institute of the Caribbean. The great cultural diversity of the region has bequeathed to its people ways of being, seeing, knowing and doing that are informed by places of origin, historic conditions of arrival in the Caribbean and encounters with other cultures in this space. This body of experience, know-how, wisdom and values constitutes ‘traditional knowledge’ which has shaped the people and cultures of the region. In the movement of peoples throughout the Americas, the Yard has been at the core of a lifelong learning space – from womb to wake – and represents, therefore, a valuable repository of traditional knowledge which, if tapped, could contribute significantly to a culturally coherent path for Caribbean development.

Through creating intersections between traditional knowledge system experts and academic workers, Caribbean Yard Campus aims to produce culturally relevant approaches to development challenges in the region. This is realized through the co-ordination of various learning opportunities and participatory events for persons of all ages. From our many collaborative events with our yards to our Rainy season and Dry season programmes and community outreach projects, the need for mutual aid work becomes more evident to us. Some of the courses we offer are: Nou Ka Pale Patwa: Conversational Kweyol; Planting People: Agro-based Sustainable Livelihoods; and Panchayat: Co-operative Development and Community Organising. Our One Yard Tour 2019 is scheduled to journey through Guyana and Suriname. We continue to work towards the development of educational content, methodology, ownership, authority and ultimately, empowerment in a knowledge-based Caribbean society.

ABOUT THE VISITORS:

Dr. Ben Braithwaite has a PhD in Linguistics, and has worked with deaf communities around the Caribbean on language rights, language documentation, and education over the last 12 years, during which time he has been Lecturer in Linguistics at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago. He has published widely in international academic journals on Caribbean sign languages and linguistics, and has received grants for sign language research and documentation work in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Honduras, Colombia and the Cayman Islands. He coordinates a programme in Caribbean Sign Language Interpreting at the UWI.

Johannah-Rae Reyes is an educator, researcher, activist, and administrator, with a BSc in Geography from the University of the West Indies. She currently works with Caribbean Yard Campus to provide innovative, transformative training in areas of Caribbean traditional knowledge, and is directly involved in the teaching of Trinidad and Tobago Sign Language. She has experience as a sign language interpreter, has carried out sign language research in Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana, and has written about issues facing Caribbean deaf communities for publication.

Dr. Braithwaite and Ms. Reyes are currently working on language documentation and educational resource development in Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago and Providence Island. In collaboration, with different Deaf organisations in the region along with ICT developers, Startl Reality, Caribbean development organisations: Lloyd Best Institute and Caribbean Yard Campus, the goal is to redefine what regional integration and inclusion could mean in contemporary times.

Go to Costa Rica and you’ll most likely expect to speak to people in Spanish or English. But in a city called Limon there is a community of Jamaican descendants who speak what is called Limonese Creole – a dialect of Jamaican Creole.

Dr Tamirand de Lisser, a member of the Guyanese Languages Unit (GLU) and a linguistics lecturer at the University of Guyana, visited Costa Rica in August 2018 for the 22nd Biennial Conference of the Society of Caribbean Linguistics (SCL), held in collaboration with the Society for Pidgin and Creole Languages (SPCL) at the Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (UNA) in Limon and Heredia.

Herself Jamaican by heritage, Dr de Lisser shares some of her experiences and explains how what she discovered could help influence the work of the GLU in Guyana…

How did the opportunity to visit Limon come about? Had you heard of them before you went?

The visit to Limon was organised as this was a designated host site of the conference. Unfortunately I had no idea that the people of Limon spoke a language called Limonese Creole, which is a dialect of Jamaican Creole. If I had known I could have prepared beforehand, which would have included taking copies of my books for the community. It’s also unfortunate as this is my area of interest and I had no idea that it existed. But so it is, you live and you learn… no regrets!

Tell us a bit about this community i.e. how they came to be there.

Jamaican migrant workers went to Limon to work on the railways and banana plantations and managed to maintain their language.

From a linguistic perspective, what was the most exciting part about the visit?

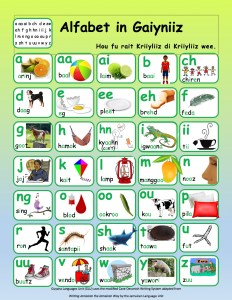

The realisation that this community existed and that linguists at the UNA are moving forward to develop and give status to the language e.g. establishing a writing system and alphabet, working on descriptive grammars, promoting positive attitudes towards preservation of the language etc.

What linguistic challenges (if any) are they still dealing with in the community?

The linguistic challenges they are facing are similar to those of many Caribbean communities e.g.

– Negative attitudes towards the language, primarily among the younger generations

– Restricted domains of use (mainly at home among families and friends)

– Suppressing the use of the language in schools/education in general

– Non-recognition of the language as a language by the government

How does the visit relate to your work in Guyana/Jamaica and with the Guyana Languages Unit?

The visit is very relevant to my work and research interests in Guyana and Jamaica, and in particular the works to be carried out by the Guyanese Languages Unit. As the challenges faced by the Limonese-speaking community are similar to those faced in Guyana, the GLU can use this as an example and implement similar procedures and mechanisms for uplifting the status of the Guyanese Creole language. We could partner and collaborate with the linguists at UNA on various research initiatives for the holistic development of Caribbean Creoles.

Do you plan to keep in contact with the community, visit again or follow up in any way?

I plan to keep in contact with the community primarily via the linguists at UNA. Collaborating on linguistic research with this community is definitely a priority for me. I would love to visit again, and to follow up on the progress of the linguistic developments of the community. I would also like to make a gift available to the community in the form of my translations – Di Likl Prins and Alis Advencha in a Wandalan, which are written in Jamaican Creole but to which they will be able to relate.

This address was made by the coordinator of Fos Klaas, Janice Imhoff, at the inaugural graduation ceremony for the group, which aims to promote the usage of Guyanese Creole in writing and society more widely.

On an evening resembling this one, in 2017, the University of Guyana created history with its first-ever course titled An Introduction to Writing Guyanese Creole. Its criteria for selection were a basic primary education. I liked that! It meant anyone just knowing to read and write could walk through the university door. On the last day of class, Tiicha Charlene suggested we form a group. And so, UG fos Kriiyoliiz kors gave birth to a baby we called Fos Klaas: Guyanese Creolese Advocates.

This however was no ordinary baby. It embodied 14 spirits representing the 14 students who were eager to transfer all we learnt to the rest of our beloved Guyana. Yours truly is the coordinator for this first year and we will be rotating this leadership. So, here I stand, to bring you greetings and to warmly thank the University of Guyana, especially our three teachers – Charlene Wilkinson, Dr. Tamirand De Lisser, and Dhanaiswary Jaganauth – for making our birth equally historic… Awi diiz jomp, plee skuul, lil ABC, big ABC, fos standard an awi miit aal di wee to yuuniivorsitii, an tonait, awi iz fo get wi sorfitiikeet dem. Tangk yu a-plenti.

Ladies and gentlemen! This baby is still growing. We are still being nurtured by our “parents”, each bringing their unique growing-food to help us through the creeping stage. Each “parent” is helping us to develop firm walking legs, so that while we have many stumbles and falls, we will be able to get up and continue to acquire skills, and so become responsible Guyanese Creolese advocates.

Fos Klaas, like all babies, has a mind of its own. If you don’t believe a baby has a mind and knows what she or he wants, think again. Put down a baby who wants to remain cuddled, or try to pick up a toddler who has found the glory of walking… iz sheer woriiz.

So, Fos Klaas has many plans and dividing them into short and long term may not be the ideal thing. For example, mastering writing in the Guyanese Raitin Sistem, perfecting the art of transcription and translation from English to Creolese, and vice versa, all start as short-term plans but will continue well into the long term. Also, acquiring data collection skills will start in the short term and continue into our long existence.

What we know is that through both our long and short-term plans, we will be challenging some misconceptions about Guyanese Creolese. I will briefly mention three.

First misconception: that the Creolese language is bad English in action, and it is a poor man’s play thing. No such thing! Bad English is bad English! Don’t use it to write Creolese. Guyanese Creolese, developed by our ancestors, has structure.

Second misconception: teaching the Guyanese Writing System will confuse school children who already have trouble learning to “speak properly”. That, ladies and gentlemen, means speaking the English language correctly. Maybe, the real question to ask is: why did the children have difficulty in the first place!

Third misconception: that the writing system is meant to regularize the different varieties of Guyanese Creoles into one standard Creole. Let us pause here… the Guyanese Writing System will do no such thing. It has no such intention. So whether you speak the Creolese of the African villages, or of the sugar estates, or of the urban working class, or whichever type of Creolese you speak, all the writing system will do is help you write it just the way you speak it. So if for the English word ‘we’ you say ‘wii’, ‘awii’ or ‘abii’, you will write it likewise.

One of our definite long-term plans is to, one day soon, gallop enough running speed so we can lift off and fly. To where are we flying? To meet with other groups, like the already established Informal Working Group, and the soon to be established Guyanese Languages Unit. Together we hope to advocate for the Creolese language to become an official language, right alongside the English language, not in front of it (even though madam chairperson that mightn’t be a bad idea!), but definitely not behind it – where it is now and where it is not being taken seriously. We want it accepted as a language with equal respect.

Gone must be the days when those who speak Creolese hear their mother tongue ONLY through the telecommunication giants who use their language in advertisements to enrich themselves. Gone must be the days when their mother tongue is heard on the drama stage at the National Cultural Centre for actors to receive awards predominantly for cheap melodramas or slapstick comedies. And gone must be the days when the only time politicians seem to find the mother tongue useful is when they seek electoral votes. Those who speak ONLY Creolese must have their voices heard and their writings read and accepted in our legal system, our education system and in our health system. “Wa gud fo di guus mos gud fo di gyanda, ya!”

In closing, may I ask you to imagine this: Students about to take an examination – for example, the one we once called Common Entrance. Imagine the invigilator saying, “Raise your hand if you want to do this examination in the English language… And raise your hand if you want to do this examination in Guyanese Creolese”. And then she concludes, “All those who can do this examination in either language say, yes!”

Yes! This we must accomplish…. in my lifetime and in yours.

[NB: This is an edited version of a previously published post.]

By Janice Imhoff, Coordinator, Fos Klaas

Very high energies were released when the University of Guyana (UG) held its course: Introduction to Writing in Guyanese Creole. This made history: one, because it was the first of its kind after more than a half century of UG’s existence; and two, it must be considered among the firsts of all other sincere attempts to build upon a post-emancipation creation.

Those energies led a group of participants to form Fos Klaas (First Class). This is not yet the definitive name; others, such as Creolese Language Activists, either as an extension or a replacement, are being considered. The group’s philosophy and its main objectives have not been finalised. Fos Klaas has 13 members: 9 females and 4 males with ages ranging from the 20s to 70s. Our three Creolese teachers – Charlene Wilkinson, Dhanaiswary Jaganauth and Dr. Tamir De Lisser – are ex officio members. We boast inclusivity! We reflect the diversity of our Guyanese heritage by way of race/ethnicity, geographic location, occupation and more. Our visually challenged participant used Braille to write Creolese!

So, what are some of Fos Klaas’s plans? For this quarter, we’re heading to Parika for our first data-collecting exercise. This was organised by one member, Robert Samaroo. Next is a trip to University of Guyana’s Berbice Campus, Tain. There we will meet and collaborate with other Creolese-speaking enthusiasts. Finally, in 2018, we’ll publish a booklet titled Why a Guyanese Writing System? and develop a working relationship with the Informal Working Group for Language Policy at UG.

These combined efforts are meant to agitate for a Guyana language policy, the pillars of which must be the acceptance of Creolese as an official language, and the introduction of multilingualism alongside English Language into our education, legal and social systems, throughout the Guyanese community.

Fos Klass is currently open only to members of the Introduction to Writing in Guyanese Creole course, but may open up in future. Sign up to our newsletter for more updates.