This address was made by the coordinator of Fos Klaas, Janice Imhoff, at the inaugural graduation ceremony for the group, which aims to promote the usage of Guyanese Creole in writing and society more widely.

On an evening resembling this one, in 2017, the University of Guyana created history with its first-ever course titled An Introduction to Writing Guyanese Creole. Its criteria for selection were a basic primary education. I liked that! It meant anyone just knowing to read and write could walk through the university door. On the last day of class, Tiicha Charlene suggested we form a group. And so, UG fos Kriiyoliiz kors gave birth to a baby we called Fos Klaas: Guyanese Creolese Advocates.

This however was no ordinary baby. It embodied 14 spirits representing the 14 students who were eager to transfer all we learnt to the rest of our beloved Guyana. Yours truly is the coordinator for this first year and we will be rotating this leadership. So, here I stand, to bring you greetings and to warmly thank the University of Guyana, especially our three teachers – Charlene Wilkinson, Dr. Tamirand De Lisser, and Dhanaiswary Jaganauth – for making our birth equally historic… Awi diiz jomp, plee skuul, lil ABC, big ABC, fos standard an awi miit aal di wee to yuuniivorsitii, an tonait, awi iz fo get wi sorfitiikeet dem. Tangk yu a-plenti.

Ladies and gentlemen! This baby is still growing. We are still being nurtured by our “parents”, each bringing their unique growing-food to help us through the creeping stage. Each “parent” is helping us to develop firm walking legs, so that while we have many stumbles and falls, we will be able to get up and continue to acquire skills, and so become responsible Guyanese Creolese advocates.

Fos Klaas, like all babies, has a mind of its own. If you don’t believe a baby has a mind and knows what she or he wants, think again. Put down a baby who wants to remain cuddled, or try to pick up a toddler who has found the glory of walking… iz sheer woriiz.

So, Fos Klaas has many plans and dividing them into short and long term may not be the ideal thing. For example, mastering writing in the Guyanese Raitin Sistem, perfecting the art of transcription and translation from English to Creolese, and vice versa, all start as short-term plans but will continue well into the long term. Also, acquiring data collection skills will start in the short term and continue into our long existence.

What we know is that through both our long and short-term plans, we will be challenging some misconceptions about Guyanese Creolese. I will briefly mention three.

First misconception: that the Creolese language is bad English in action, and it is a poor man’s play thing. No such thing! Bad English is bad English! Don’t use it to write Creolese. Guyanese Creolese, developed by our ancestors, has structure.

Second misconception: teaching the Guyanese Writing System will confuse school children who already have trouble learning to “speak properly”. That, ladies and gentlemen, means speaking the English language correctly. Maybe, the real question to ask is: why did the children have difficulty in the first place!

Third misconception: that the writing system is meant to regularize the different varieties of Guyanese Creoles into one standard Creole. Let us pause here… the Guyanese Writing System will do no such thing. It has no such intention. So whether you speak the Creolese of the African villages, or of the sugar estates, or of the urban working class, or whichever type of Creolese you speak, all the writing system will do is help you write it just the way you speak it. So if for the English word ‘we’ you say ‘wii’, ‘awii’ or ‘abii’, you will write it likewise.

One of our definite long-term plans is to, one day soon, gallop enough running speed so we can lift off and fly. To where are we flying? To meet with other groups, like the already established Informal Working Group, and the soon to be established Guyanese Languages Unit. Together we hope to advocate for the Creolese language to become an official language, right alongside the English language, not in front of it (even though madam chairperson that mightn’t be a bad idea!), but definitely not behind it – where it is now and where it is not being taken seriously. We want it accepted as a language with equal respect.

Gone must be the days when those who speak Creolese hear their mother tongue ONLY through the telecommunication giants who use their language in advertisements to enrich themselves. Gone must be the days when their mother tongue is heard on the drama stage at the National Cultural Centre for actors to receive awards predominantly for cheap melodramas or slapstick comedies. And gone must be the days when the only time politicians seem to find the mother tongue useful is when they seek electoral votes. Those who speak ONLY Creolese must have their voices heard and their writings read and accepted in our legal system, our education system and in our health system. “Wa gud fo di guus mos gud fo di gyanda, ya!”

In closing, may I ask you to imagine this: Students about to take an examination – for example, the one we once called Common Entrance. Imagine the invigilator saying, “Raise your hand if you want to do this examination in the English language… And raise your hand if you want to do this examination in Guyanese Creolese”. And then she concludes, “All those who can do this examination in either language say, yes!”

Yes! This we must accomplish…. in my lifetime and in yours.

[NB: This is an edited version of a previously published post.]

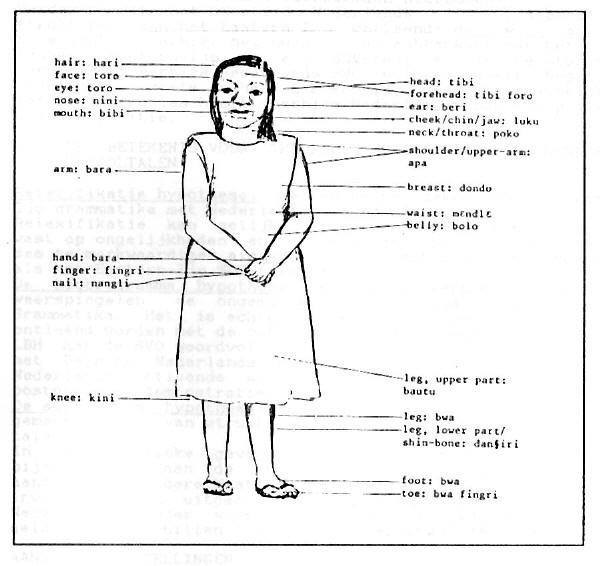

Explaining the second point further, Professor Robertson says: “The language contained more than ten times the number of West African derived forms that could be found in any Caribbean Creole language. All the basic words for body parts and the more central functions like speak, walk, drink, run cold be traced directly to this West African language group. No other Creole language of the Caribbean contains such a high percentage of African derived forms.”

Explaining the second point further, Professor Robertson says: “The language contained more than ten times the number of West African derived forms that could be found in any Caribbean Creole language. All the basic words for body parts and the more central functions like speak, walk, drink, run cold be traced directly to this West African language group. No other Creole language of the Caribbean contains such a high percentage of African derived forms.”