The deadline for the Part-time Remote Research Assistant positions has been extended to Friday, 25 July 2025 (please ignore date in original add below).

For more information, visit http://shorturl.at/pX6Wp

The deadline for the Part-time Remote Research Assistant positions has been extended to Friday, 25 July 2025 (please ignore date in original add below).

For more information, visit http://shorturl.at/pX6Wp

By Michael McGarrell

In the aftermath of the devastating fire that claimed the lives of 20 young Indigenous girls and a little boy in the Mahdia Secondary School dormitory, my heart aches for the families, communities and everyone affected by this immense loss. The tragedy not only highlights the importance of fire safety but also calls attention to the cultural issues faced by young students living far away from their families and familiar environments.

For many Indigenous students, attending schools far from their small communities means leaving behind the comfort of home, traditions and the support of their close-knit families. Living in dormitories, although necessary for educational opportunities, can be an incredibly challenging experience, with feelings of isolation and homesickness prevailing. Having been a dormitory student myself, I experienced it all.

Preserving cultural identity and fostering a strong sense of belonging is vital for the well-being of these students. Cultural immersion plays a fundamental role in their growth and development, and when it is disrupted, feelings of alienation can ensue. The tragedy has reminded us that schools must embrace and integrate indigenous cultures into their educational framework to provide students with a safe space where their traditions and values are respected, cherished and practiced.

Living in dormitories, although necessary for educational opportunities, can be an incredibly challenging experience, with feelings of isolation and homesickness

In the wake of this heart-wrenching event, the affected communities and schools must come together to heal and rebuild. The implementation of vital measures by the Government is also required to tackle cultural concerns and provide support to the grieving families. Grief counseling and mental health services should be made available to the students, their families and the school community. The trauma from the fire will leave a lasting impact, and providing professional support is essential in the healing process.

School staff and administrators should undergo cultural sensitivity training to better understand the unique challenges faced by Indigenous students. Sensitization to cultural norms and traditions will foster empathy and create a more supportive learning environment. Immediate and ongoing assistance should be offered to the bereaved families, and regular training sessions organized for school administrators, staff and ancillary personnel to enhance their ability to manage the school and dormitory effectively.

Collaboration with the local Indigenous communities is crucial. By engaging community leaders and elders, the schools can gain valuable insights into the students’ cultural backgrounds, allowing for a more inclusive and culturally sensitive approach to education.

School curricula should be revised to include Indigenous history, language and cultural practices. By promoting Indigenous knowledge and traditions, students can feel a stronger connection to their heritage, even when living away from home.

Safe dormitory conditions are critical for the well-being of children. Fire safety measures in school dormitories must be reviewed and enhanced to prevent such tragic incidents in the future. Adequate precautions and emergency preparedness can provide peace of mind to both students and their families and this must be taken into consideration.

School curricula should be revised to include Indigenous history, language and cultural practices.

Efforts should be made to provide scholarships and support to Indigenous students to reduce financial burdens and make education more accessible. Ensuring that students have the opportunity to learn in their own communities whenever possible can be transformative. With the advent of better communication technology, we can have smart classrooms within communities so students can stay at home and study.

The loss of these young lives is an unimaginable tragedy, and no words can ease the pain felt by the families and communities affected. However, by addressing the cultural issues and actively supporting the healing process, we can strive to create a brighter future for Indigenous students who must overcome immense challenges while seeking an education away from home.

Let us honor the memory of these young souls by fostering a society that values and celebrates cultural diversity, ensuring that no student feels detached from their roots and that education remains a pathway to empowerment and growth for all. Together, we can build a more inclusive, compassionate and culturally enriched educational landscape that nurtures and uplifts every young mind, regardless of their background. Let us honor them by ensuring that those responsible are held accountable and that necessary steps are taken to address the many gaps that exist into our systems.

Patamuna yamùk Nùppyattàppù

Iyeppyattàppù pantomù

Patamuna maimu pe Kappon yamùk pùikattàtok, tukke mule yamùk uyatùppù Mahdia po 22 May 2023 yattaino pàkànsau Guyana Language Unit (Guyana yawon Mayin yamùk yennài) uya usenupannà tok piyattàpù, sa’man pe ma’le mayin ittu tok ipàkàlà pe Sàlà usenupannà tok wepyattàpù màlà Covid 19 uya pata yeposak yattai, molopai Sàlà tepoik tok wechi pata mattanù’ nài nan molonka’nùpù che.

Asa’là mayin ittunnan (Patamuna molopai Enkelechi tukaik), molopai Patamuna yamùk tùusenupa kon pàk waikattau (iken po) tùwesan yamùk pokonpe tok we’wotokomappù; màlà yentak lùiwa asa’là tùmaimu kon ittutok tùuya nokon I’nnapailà lùiwa pàk. Sàlà uya tok yenupasak, eichilà tùtonpa kon pùikatàtok pe tok uya ikasa làkku molopai Patamuna yamùk yeselu yau ikasa mayin yekama pàk.

Kappon yamùk UG (University of Guyana) (I’napailà Usenupan pata) tawon kon molopai Potolù yamùk, Patamuna pe tùuseluppasan pen, utàsak Patamuna yamùk patassek yak yattai tok maimu yekamannan pe tok wettok pe tok usenupasak nai’nùk.

Sàlà usenupantok yau, enupannan yamùk nettai:

(a) Ovid Williams, Patamuna Kàyikkù,

(b) Charlene Wilkinson nen uchi imaimu yekamanài, Molopai tok pùikattàn’nan mayin yamùk nàlà itunnan nettai:

(c) Louisa Daggers, Amerindian Research Unit yennài,

(d)Ticha Hubert Devonish tukke mayin yamùk ittunài; ICCLR, UWI

(e) Debbie Hopkinson, Àsà pe pata umattasak yau Kapon yamùk wemapù yennài

(f) University of Guyana uya nàlà sàlà usenupantok wekkutok pe tok lepappù man patasek ke Turkeyen Campus po. University of Guyana tau Potolù pe tùwesen uya $300,000 yentai pùlayatta tùlùppù, Patamuna yamùk usenupatok wekkutok pe.

(g) Maylene Thomas, Lokono/Arawak pachi wechipù tok yeipattànài pe; molopai.

Sàlà usenupantok wepyattà pù June 10th motapai, asakùlà’ne sattete molopai suntayakka kaichalà, 09:00 ko’làma motapai 12:00 peleppochi pùkkùyak, tamu’nawàlà 20 hours kaichalà.

Usenupantok wechippù sàlà yamùk pàk:

a.)

– Ikasa Mayin yapulà tok

– Uselupan pàk, molopai yà’làkasa I’nnapailà lùiwa mayin ituche we’nàtok pàk

b.) Tùwekkusan pata yamùk yau kupù iyettok kasa màlà yentak lùiwa mayin ittutok pe.

c.) Mayin yekama tùulon maimu yau.

Ànùklà uya sàlà usenupantok Patamuna yamùk maimu pàk yempàtù iche we’nà pen nainùk. I’nailàlà enkelechi pe tùwesan yamùk kùlotau là. GLU wechi màlà tùulon mayin yamùk yau sàlà yekwa wotoko wepyattà iche Guyana yau: Alekuna, Akawaio, kali’na, Creolese, Lokono, Makuchi, Wai-Wai, Wapiyana molopai Walau.

The Patamuna Team Initiative

Introduction:

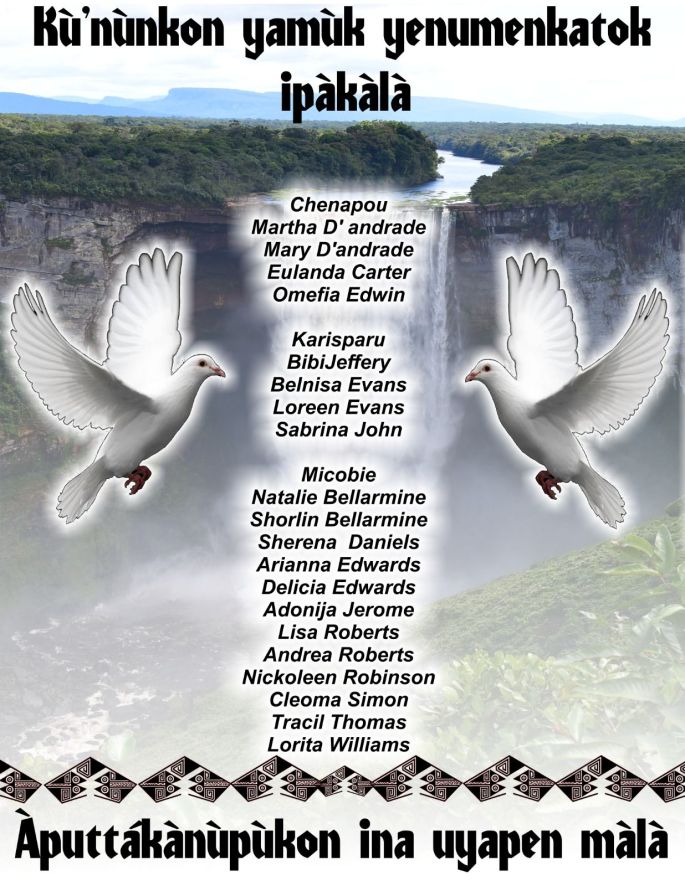

In response to the tragedy following the Mahdia fire of May 22, the GLU initiated a workshop in Emergency Language Facilitation, a continuation of the GLU’s disaster management response, begun during the COVID-19 Pandemic. A select group of bilingual speakers (Patamuna and English), all native Patamuna speakers currently pursuing tertiary education in Region 4, worked with facilitators to develop their bilingual competence. This was to prepare them to be reasonably ready to provide appropriate and culturally sensitive interpretation service during any intervention of UG and other professional non-Patamuna speaking team(s) in the affected Patamuna communities and beyond.

The chief facilitators were Ovid Williams, Patamuna translator and interpreter and Charlene Wilkinson, Language Arts specialist and Coordinator, GLU. Our support professionals were Louisa Daggers, Coordinator of the ARU, Prof. Hubert Devonish, linguist, ICCLR, UWI and Debbie Hopkinson, Head of the Institute Of Human Resilience, Strategic Security And The Future, UG. The Faculty of Education provided the space on the Turkeyen Campus, Maylene Thomas of the Lokono nation provided the meals, and the Vice Chancellor’s Office dedicated over $300,000 for this initiative.

The workshop began on Saturday, June 10 and ran for 4 consecutive weekends from 9:00 am to 12:00 pm with a half hour break for lunch, amounting to 20 hours.

The general areas covered were:

(a) Language Awareness:

– Self-reflection and self-assessing of language competence

– Recognizing variations across communities

(b) Drama routines to develop language for community language needs:

(c) Translation and Interpretation challenges

One should not underestimate the potential long term cultural benefits to the Patamuna language and culture in this sustained and guided process of using the language in domains that are usually dominated by English. The GLU looks forward to similar initiative in all the other native languages of Guyana: Arekuna, Akawaio, Carib, Creolese, Lokono, Makushi, Wai Wai, Wapichan and Warau.

By Charlene Wilkinson, translated in Patamuna (above) by Vickiola Aaron

The Guyanese Languages Unit (GLU) supports President Irfan Ali’s call for a Commission of Inquiry (COI) into the tragedy at Mahdia. We suggest the following terms of reference:

1) To investigate the specific circumstances leading up to and contributing to the deaths of 19 children at Mahdia, with a view to making recommendations for changes which would prevent a recurrence of such an event across all such school dormitories in the country.

2) To investigate the general conditions of school dormitories across the country with a view to instituting and enforcing Codes of Practice for all buildings, including the norms of the International Standards Organization (ISO) for fire safety and occupancy.

3) To make recommendations that would improve the quality of the living conditions and educational experience of the children occupying these dormitories; these recommendations would include but not be limited to the financing, physical plant, adult supervision, safety, security, food, and house rules for those living in the dormitory facilities.

4)

(a) To investigate whether and when there might be better options for children in remote areas, to avoid them being separated from their parents and communities in order to receive an education.

(b) To make recommendations as to what these options might be, and how, where and when they might be implemented.

5) To investigate and make recommendations on any other matters such as drop-out rates for Indigenous children and exam pass rates which reflect Guyana’s response to the right to education of children from these remote communities as the commission might consider relevant.

6) To investigate more broadly the arrangements for the provision of education to children from these remote communities and to make recommendations concerning the maintenance of community language and identity as part of that education.

7) To consider recommendations on government funding for:

(a) better equipped schools and

(b) better paid teachers.

This letter is a response to an article written by Vishani Ragobeer and published in The Guyana Chronicle on 4 June 2023. To hear this letter read in Patamuna, please scroll down.

Dear Ms. Ragobeer,

It gives me great pleasure to respond to the article you wrote about the tragic fire that claimed many lives and traumatized many others. Your comments were particularly intriguing when you discussed your experiences in Karisparu. As a resident of region 8, I can attest that many people have negative perceptions of schools in the interior. Inadequate infrastructure, a shortage of qualified teachers, and a limited range of educational options are just a few of the problems that are thought to increase the likelihood of suffering from their socioeconomic makeup and geographic isolation.

In order to increase access to essential services and foster economic growth, I advise that the government make investments in infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and sanitation facilities. Public-private partnerships, international aid and other funding sources are viable options for achieving this.

Education departments often focus on luring outsiders to live and work in rural areas instead of recruiting teachers from interior, but this can be improved by training prospective workers in rural areas. Education providers may also consider teaching areas of the curriculum or specialist skills in remote areas by non-qualified staff. Furthermore, technology can be applied to enhance service accessibility in the field of education, where online learning platforms can be used to provide access to education.

All for your information,

Thank you.

Nicky Edwin

Listen to the letter read in Patamuna

This letter is a response to an article written by Vishani Ragobeer and published in The Guyana Chronicle on 4 June 2023. To hear this letter read in Patamuna, please scroll down.

Dear Miss Ragobeer,

In response to your article dated 4 June 2023, I commend you for highlighting several sore areas that affect hinterland communities. First, I would like to point out that the problems are not unique to Guyana, therefore the government can research and discover how other nations have resolved similar problems in the past and then apply those strategies to curb the problem.

You mentioned geographical challenges that continue to affect us in the interior. Although I agreed with most of the alternatives you mentioned in your article, I would like to share my opinion on some of them. You referred to President Ali’s consideration of building schools in each village to accommodate high-school children. Realistically speaking, I do not think this will solve the problem since most of the villages have a limited number of students and sometimes there are no high-school-age children in an area.

I believe that providing a dormitory in the most populated area is still the best option, however additional safety protocols need to be implemented, such as the installation of fire alarms in the building and smoke detectors, employment of more house parents, employment of counselors to work at schools, and maybe a center for parents to stay at when they visit their child/children during the school term. I have heard parents complaining about not having a place to stay when they bring their children back to the dorms, therefore they cannot spend more than one day with their children until the term ends, when they come to take their children home.

Another challenge that we face in the interior is the language barrier. Language is very important in education, to interact in the learning environment and comprehend the content of the curriculum. Unfortunately, some learners have language difficulties. We all know that English is the second language of Indigenous people, as such it is difficult to teach content or a concept to a learner that is now learning to speak English. Although speaking in our dialect is not limited in schools, it is difficult to teach content that was learned in English in our dialect, for students to understand in Patamona and then write it in English when they are asked to. To tackle this issue, I think parent support groups can be implemented where parents can freely share how they have dealt with similar issues. Government can provide incentives for such groups to attract more members as well as to maintain the group.

Additionally, internet connectivity has been significantly affecting education in the interior since students and teachers in these areas are expected to take the same workload as those in Georgetown. Students are expected to do online research and download templates for technical drawing and other subject areas. Teachers are expected to upload samples of SBAs (School Based Assessments), and sometimes submit a record if the need arises for online submission. Although these activities are done by those that can access E-gov wifi (government-funded internet), the connection is mostly unstable. So if ten people are connected to the internet, just imagine the frustration you will have to endure because of not being able to complete a task. If you are sitting in the government office while reading my letter I am pretty sure you will understand what I am talking about, but the e-gov internet connection is 10 times poorer in the hinterland regions compared to Georgetown.

Therefore, I believe that the government needs to upgrade the system to some other service provider that can work better in rural areas. There are private businesses that provide internet services in the village, however they are very expensive and most of us cannot afford them due to several economic challenges that you mentioned in your article. Therefore, I think that government needs to change and upgrade the internet provider in the hinterland communities so that we can keep abreast with what’s happening in the rest of Guyana.

I am pretty sure that most of my indigenous brothers and sisters are not aware of the ONE GUYANA initiative that was launched years ago. This is just one example of how clueless we are in the absence of a tool that keeps the global community connected.

In closing, I would like to commend you once again for boldly voicing many of the challenges that affect Indigenous people.

Sincerely yours,

Marcia John

Patamona pachi from Paramakatoi

Listen to the letter read in Patamuna

This letter is a response to an article written by Vishani Ragobeer and published in The Guyana Chronicle on 4 June 2023. To hear this letter read in Patamuna, please scroll down.

Dear Ms Ragobeer,

In response to your letter dated June 2023 regarding the tragic Mahdia incident, where 19 lives were lost, I would like to express my concerns and offer some recommendations for the authorities involved in the planning and implementation process of addressing this heartbreaking issue.

Firstly, I would like to address your statement regarding the provision of support not only in the present but also in the long term. As an indigenous woman from Region #8, I possess a deep understanding of the region, its landscapes and its geographical challenges. Most of the affected families come from areas that can only be accessed by air transportation, which is both logistically and financially demanding. Therefore, I would like to inquire about the feasibility of sustaining this support in the long term, particularly for communities where the families of the victims reside. Given the region’s geographical constraints, constant access to these areas becomes difficult and expensive. Will it be practical to travel frequently to provide support to communities such as Karisparu, accessible only by helicopter, or Chenapou and Micobie, reachable by aircraft?

Moreover, we must consider the economic factors at play, as many individuals in these communities are unemployed due to limited job opportunities and lack of resources. This further complicates their ability to meet their basic needs, while the families of the deceased victims are grappling with finding means to provide for themselves. This additional burden exacerbates the challenges they are already facing.

You mentioned that His Excellency Honorable Irfaan Ali suggested the establishment of schools in these areas to cater to students in their own hometowns. While this may sound appealing to the public, it may not be feasible as building schools for a small number of students may not be cost-effective. Instead, such resources could be utilized to address other crucial aspects of our country’s development, such as improving internet and mobile connectivity, enhancing infrastructure, addressing electricity and water supply issues, and strengthening healthcare and education systems, especially in the hinterland regions.

Considering the prevailing political instability in the country, I sincerely hope that the current administration will fulfil its promise to provide ongoing assistance without bias. It is my wish that even in the event of a change in government and administration, support for the bereaved families will continue uninterrupted.

In conclusion, as Indigenous Peoples of Guyana, we often find ourselves marginalized and underrepresented. Therefore, I urge the government to consider it their utmost obligation to provide support in all forms without any form of discrimination or favoritism. I hope that my concerns and suggestions will be taken into consideration and incorporated into future planning as we collectively offer support and assistance to the families of the deceased and the survivors. All for your information.

Respectively yours,

Vickiola Aaron

Paramakatoi Village

North Pakaraimas

Region #8

Listen to this letter read in Patamuna

It was a privilege for me to attend the International Mother Language Day multilingual education session hosted by the Guyanese Languages Unit on February 21, 2023, under the theme: “Multilingual Education: a necessity to transform education”. I am delighted to be a Guyanese citizen since our nation has a wide variety of languages. In addition to English, Creole, Spanish, and Portuguese, there are approximately 10 Indigenous languages spoken here, for example Wapichan, Patamuna, Warau, Carib, and Arawak. But many of these languages are at risk of extinction, and those who speak them are frequently stigmatized.

In order to preserve our linguistic legacy and guarantee that all Guyanese children have the chance to study in their native language, the workshop emphasized the value of multilingual education. Numerous advantages of multilingual education for pupils have been demonstrated, including higher cognitive abilities, better academic performance, and a stronger sense of cultural identification. The workshop’s emphasis on Indigenous peoples’ voices piqued my curiosity as these voices are not frequently heard in mainstream culture. The workshop gave Indigenous peoples a forum in which to explore the value of multilingual education for their communities and to share their experiences.

I am appreciative that the Guyanese Language Unit put together this crucial session. It was an eye-opening event that motivated me to consider the native languages and cultures of our nation. I am dedicated to supporting this vital effort because I think that multilingual education is crucial for changing the way that education is provided in Guyana. My parents spoke Creolese when I was growing up. When we visited relatives in Georgetown, I tried my best to speak standard English, with many errors though. My mom was embarrassed and would usually hit me. However, I was taught proper [English] grammar and tenses to boost my speech. I now realize that Creolese was my mother tongue and I cannot speak it.

Multilingual education can serve to foster tolerance and understanding between many cultures in addition to the advantages already highlighted. Bilingual education is Guyana’s educational future. It is a method to protect our language history, guarantee that every child has the chance to thrive, and create a society that is more accepting and understanding. I kindly request that multilingual education be supported by the government and educational institutions so that we may all take advantage of its numerous advantages. It was a joy to hear that our Vice Chancellor, together with my lecturer Ms. Charlene Wilkinson, has decided to earnestly make representations for our Indigenous peoples.

Christine Rupi

This blog was written as part of an assignment for Use of English, a module within the Department of Foundation and Education Management at the University of Guyana.

By Dr Adrian Gomes

Among the Wapichan, in the South Rupununi, Region 9, Guyana, there are some people who claim mixed Atorad or Taruma ancestry. Although Atorad and Taruma are mentioned relatively frequently in the early published sources, little is known of their histories and their languages.

One possible history of the Taruma, based on oral tradition, is that they lived on the Upper Essequibo. During the 18th (or more probably 19th) century, the Taruma migrated north- and eastward, living for some time close to the Wai Wai, with whom they had interethnic skirmishes. By the beginning of the 20th century, they had reached the forest immediately to the south of the Wapichan, living in several villages. From that time on, they were slowly absorbed by the Wapichan, apparently via intermarriage. In present-day Guyana, there is a family of mixed Taruma ancestry who live on a hill called Toronaawa, an hour’s walk from the centre of Maroranaawa, a Wapichan village of South Rupununi, Region 9.

Together with expatriate linguists, we found three remaining speakers of Taruma. Furthermore, we found that the data recorded with each of them is almost 100 percent consistent (i.e. clearly not invented or poorly remembered), and most words are very similar to those recorded in the older (19th and early 20th century) sources, thus establishing that Taruma is indeed a real language, but a moribund one.

However, the Taruma are keen to activate their passive knowledge of the language and share this with their relatives and friends. In particular, several place names in the South Rupununi are of Taruma origin. Additionally, the Taruma seem to have had an indelible influence on the material culture of the Wapichan.

All these findings, which form a historically continuous link between the Taruma and the Wapichan, are of high relevance to the Amerindian Research Unit and the Guyanese Languages Unit, both of which I am affiliated to. The collecting of these Indigenous knowledge systems will contribute a rich corpus to further study of Guyanese native languages. Thus, the goal is to continue the collaboration in documenting the languages and knowledge of the people of the Wapichan communities.

My attendance at the International Mother Language Day workshop was very rewarding and enlightening. When I entered the George Walcott Lecture Theatre I received a warm welcome, after which I was escorted to a table of brilliant people who all greeted me with a pleasant smile. I felt at ease and it was a privilege to be at such an historical event. At my table of nine I was delighted to meet two representatives from NCERD, three Amerindian people, two teachers and one student.

I joined the discussion about transferring our language and culture to the next generation. My general takeaway from that discussion is that as Guyanese we must learn to appreciate our mother languages. The highlight of the discussion was when we spoke of how we, as individuals, often times try to correct our children by insisting that they speak ‘properly’ and in ‘Standard English’. However, by doing so we are neglecting our first languages. It was concluded that the younger generation will only appreciate our native languages if we add value to them and make them meaningful. Therefore more workshops are needed countrywide to bring more awareness and further introduce these languages in schools. In that way we will be able to love and appreciate our mother languages and culture.

This blog was written as part of an assignment for Use of English, a module within the Department of Foundation and Education Management at the University of Guyana.